The 30-Year Home Mortgage Isn’t Designed for Climate Chaos

December 23, 2024

It sounded like artillery, an infiltration of a quiet suburban community in the dead of night, as Kevin Pelley stood in the dark in what was left of his yard on a bank of the Puyallup River. A combat Army veteran who served in Kuwait and Iraq, Kevin watched the storm for hours. An atmospheric river was filling the actual river, causing a flow of over 16,000 cubic feet per second, or 50 times the prior month’s average. Water washed away much of his backyard. When a large piece of soil cleaved off into the river, it fell with the force and noise of gunfire.

Bạn đang xem: The 30-Year Home Mortgage Isn’t Designed for Climate Chaos

Uncovered: Part 7

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 and Part 6.

The Pelley family — Kevin, Shauna, two cats, two dogs, eight ducks — had only lived in the house for about five weeks when the flood struck in November 2022. Their real-estate transaction, like hundreds of thousands completed in the US each year, was designed to redistribute the risk of owning a valuable, highly leveraged asset subject to the whims of fires, floods and other destructive events. The mortgage lender took no issue with the home’s proximity to the water. Closing the deal required a method for moving that weather danger away from the family and its lender. And that meant an insurer.

USAA wrote the Pelley’s home insurance plan. The family had even bought flood insurance via the federal government’s program, despite not being in a flood zone. The family did not receive payment from either one. The flood policy didn’t become active until after the river rose. Regardless of when the policy took effect, “USAA would have denied and FEMA upheld the denial because water didn’t enter the property or damage the foundation,” Kevin says.

After sign-offs from the underwriter, appraiser, loan officer, insurance agent, engineer and realtor, the Pelleys found themselves saddled with a property that was now unlivable and a mortgage that was due. Even if the family was able to get a settlement from the flood policy, it would have been less than half of what they owed their lender, leaving them with a devastating loss.

Kevin and Shauna Pelley on the foundation of their dream home in Graham, Washington, in February. The family was impacted by a 2022 flood and then another in 2023.

Video: Grant Hindsley for Bloomberg Green

In December 2023, Kevin says an official from Pierce County called: another flood was coming. After a century of minimal flooding, this was the river’s second severe episode in just over a year. County officials said that if the house wasn’t razed, they’d be responsible for any damages and pollution that came from the structure falling in the water; that bill, the family recalls, could rise to seven figures. “Pierce County worked with the property owners to discuss options to remove the home,” Christina Rohila, a public information specialist with the county’s planning and public works department, says in a statement. The family agreed, and the house was demolished. The Pelleys say their mortgage company later determined they behaved responsibly.

What was their home is now a cement slab, with bits of granite and linoleum flooring sticking out. The county sent a $38,000 bill, which incurs interest monthly. The Pelleys owed more than half a million dollars for a home that no longer existed on land that was unbuildable. Insurance, the Pelleys say, still refused to pay. Water didn’t come into the house into this second event, either, as it had been erased.

“We shed a lot of tears over this,” Shauna Pelley says. “Absolute climate change. And bad luck. I think it’s a little bit of both.” Source: Shauna Pelley

A spokesperson for USAA said the company was unable to comment specifically about the Pelleys’ case, citing a privacy policy. “In general terms, in order to have a flood policy active, you have to have it for at least 30 days,” the spokesperson said. “A flood policy is required to be in effect for 30 days prior to being active.” FEMA, which administers the National Flood Insurance Program, declined to comment on the matter, citing privacy concerns. In an appeal denial seen by Bloomberg Green, FEMA found that “while there may have been a flood in the area and the river was above flood stage, the policyholder has not presented any evidence to prove the building was damaged due to a direct physical loss by or from flood.”

Most mortgages in the U.S. are backed by the federal government, including this loan, which was backed by the Department of Veteran Affairs. In a statement speaking generally about its lending program, a spokesperson for the department says the agency encourages “servicers of guaranteed loans in disaster areas to extend forbearance to borrowers in distress.” The agency says it has started collecting and analyzing data to understand the impact of climate risk on its home loan program, but that the analysis is still ongoing and the results are not yet available to the public. The agency’s loan technicians aim to help borrowers who are working with banks and insurers, but the agency “does not have the authority to force specific actions to be taken by either entity,” it says.

A different kind of perfect storm had hit the Pelleys: volatile weather, a country failing to keep up with rising flood risk and a mortgage industry writing loans without considering the future of the environment around the home. Homeowners in Florida and California have already been trying to reconcile their mortgage duration and dwindling insurance options with neighborhoods that may not live to see 30 years. In a nation where long-term loans are the gateway to homeownership for most families, climate change is rewriting the basic assumptions about risk.

The lending industry relies on insurance to absorb some of the risk of mortgages failing. And the insurance industry is largely predicated on the idea that if a home is damaged or destroyed, a comparable structure should be rebuilt on the same spot. This model will have trouble accommodating land changed beyond recognition, no longer able to host a dwelling.

Little remains of the Pelley home, pictured in February. Photographer: Grant Hindsley for Bloomberg Green

The Puyallup River snakes through where the Pelley house stood, boasting a new ’S’ shaped curve where their yard used to be. Photographer: Grant Hindsley for Bloomberg Green

As the chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, US Senator Sheldon Whitehouse has been outspoken about the rising costs associated with climate change. “The fundamental problem here is that you have properties that in a fixed period of time are going to have no real value because of the risk of fire or flood,” says Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island who sits on the Environment and Public Works Committee.

Economists are beginning to sound warnings, urging the mortgage industry and insurers to face the risky reality that annual insurance policies cannot always be reconciled with 30-year loans. But the big business of housing hasn’t adopted climate underwriting. There’s no high interest rate penalty for buying in an area that’s a fire risk. There’s no climate credit score.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse is among those in Congress concerned with how a changing climate will impact the American people and economy. Photographer: Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post/Getty Images

The industries responsible for making sure homes keep selling are not adequately accounting for the rising but often invisible climate risk threatening American homes. That means the soaring costs due after a major weather event will land on individual consumers — and, eventually, the federal government. This feedback loop will intensify as disaster recovery costs soar and government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) must backstop more failed mortgages.

“The risk is not borne by the entity that originates the loan,” says Benjamin Keys, a professor of real estate and finance at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “The risk is borne by the US taxpayer.” And, like the Pelleys, some of those taxpayers will be left to rebuild their lives and homes on their own.

Somewhere in the backwaters of Wall Street, the Pelleys’ home loan, on a house that no longer exists, is bundled together with thousands of others into a financial instrument called a mortgage-backed security.

The entire system is de facto nationalized, buoyed by the federal government via the Federal Housing Finance Agency. That agency oversees Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which back 58% of home loans in the US. Additionally, 22% of outstanding residential mortgages are backed by agencies like the Federal Housing Authority, Rural Housing Authority, and VA. These enterprises chug along quietly, siphoning up mortgages. The FHFA system, which is only for residential loans, is the outcome of the too-big-to-fail financial crisis in 2008, where the federal government stepped in to prevent the housing crisis from bankrupting the nation.

This system assumes that those with mortgages in at-risk areas have insurance, and that the coverage is robust enough to rebuild a storm-ravaged home back to its full value. It also assumes homes that aren’t in mandatory flood insurance zones are in fact in safe areas, rather than simply the product of maps lagging behind the reality of climate change. Disasters like this year’s Hurricanes Helene and Milton threaten to upset this system, particularly when storms impact homes far off their initial path.

“There’s just not enough dollars to cover the damages,” says David Burt, who runs an investment research firm called DeltaTerra Capital that works with investors to measure and manage the fiscal risks of a changing climate. (His work also inspired The Big Short.) “People think about this as being a problem for insurers to deal with. But insurers are just risk transfer agents.”

That risk isn’t always well understood. People living inside FEMA-designated flood zones are required to buy federal insurance. But risk doesn’t end at the boundary of a government map. Outside of those areas, the vast majority of homeowners are not required to buy flood insurance, and so do not. Consequently, they are unprepared when disaster strikes. Across six states, 5.7 million single and multi-family homes most likely lacked flood insurance in counties declared “major disaster areas” after Hurricane Helene, according to an analysis by CoreLogic Inc. Five million more in the path of Milton through Florida were in the same predicament — and 2 million homes outside of flood zones were exposed to both storms.

The zones are far from perfectly determined. FEMA’s maps are supposed to capture areas with flood risk from storms that have only a 1% chance of occurring in any given year, or a 25% chance during a 30-year mortgage. They are designed to identify the highest-risk areas — where federal flood insurance policies are required—and show what the minimum flood-protection standards should be. But they’re notoriously inaccurate, unable to estimate rain-driven flooding. FEMA maps are updated continuously, and local officials can submit technical evidence supporting changes, whenever prompted by new construction, erosion or major weather events. The agency receives some 1,500 map update requests a year. In 2023, FEMA wrote up policy ideas for Congress to update the NFIP, including modernizing maps and requiring flood-risk disclosures in real-estate deals.

“Of the 10 million homes in the path of Helene, we estimated that 580,000 are in FEMA designated flood zones and there’s another 500,000 outside of FEMA flood zones but the science would suggest are quite high risk,” Burt says. There were only 460,000 National Flood Insurance Policies within the 10 million homes. “So there’s at least 500,000 high flood risk homes that simply don’t have flood insurance.”

Bat Cave, North Carolina, was hit particularly hard by flooding from Hurricane Helene. Photographer: Mario Tama/Getty Images

About a third of flood-insurance claims come from outside highest-risk zones. “No-risk zones” don’t exist, and a FEMA spokesperson says that many Americans may have an optimism bias. They understand that floods happen but doubt it will happen to them.

The federal government could mandate that every mortgage it guarantees carry flood insurance, regardless of location. It could be tacked onto the existing list of GSE requirements for lenders, which already includes things like the amount a loan can be written for, how much debt the borrower can be in, and what credit score must be met. In theory, the federal government could create new standards at any time via the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

Outside of requiring flood insurance in high risk zones, the GSEs “have assiduously chosen not to price different geographies differently,” Keys says. An area at risk of extreme heat is not punished with higher interest rates and tougher lending standards.

“Fannie and Freddie are basically these giant insurance companies. That’s where the buck stops for much of the $13 trillion mortgage market,” says Keys.

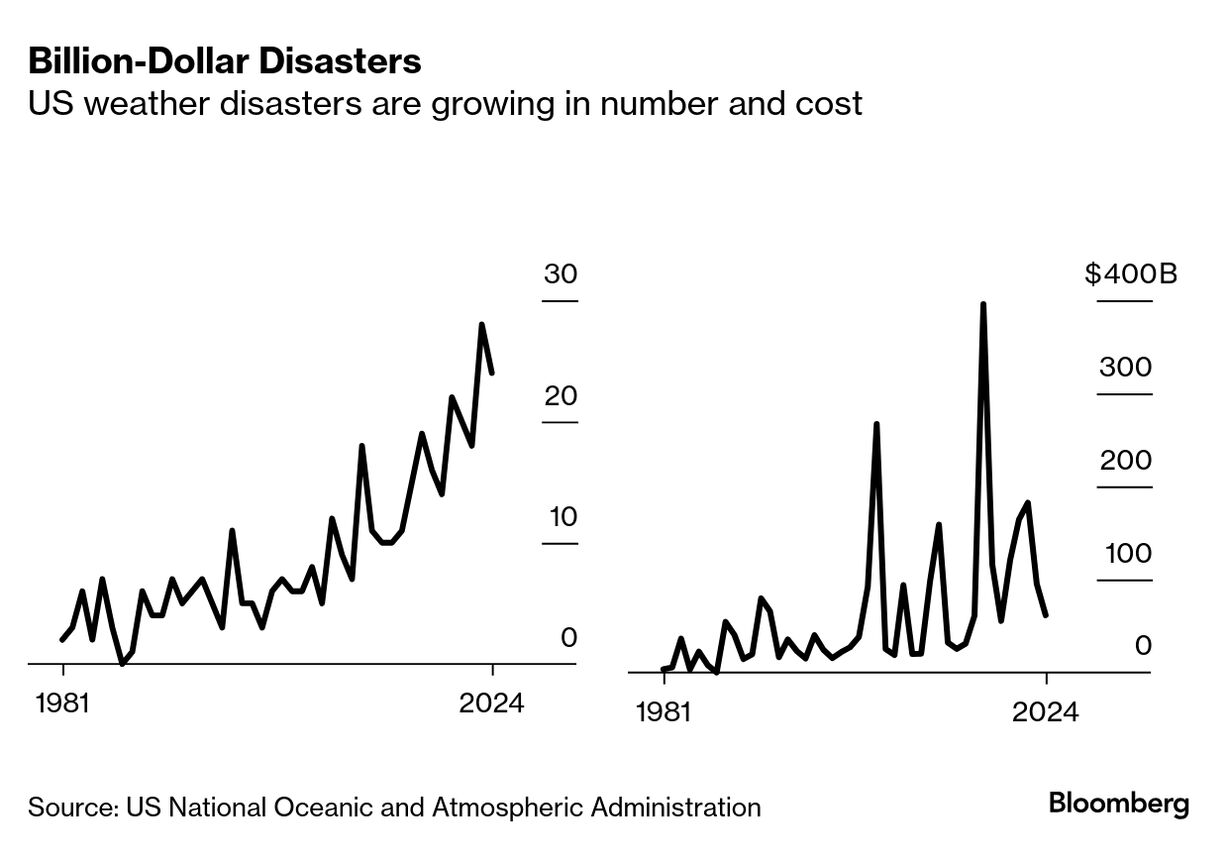

It’s an increasingly expensive world. Damages from weather disasters last year totaled $92.9 billion, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And insurance premiums are also on the rise. Insurance costs rose an estimated 13% between 2020 and 2023, adjusted for inflation, according to a study of 47 million households by Keys and Philip Mulder of the Wisconsin School of Business.

Billion-Dollar Disasters

US weather disasters are growing in number and cost

Source: US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The reasons are clear to the researchers. Recent premium increases were commonly in the most disaster-prone areas and driven chiefly by inflation and reinsurance — the policies that insurers buy to cover themselves. Reinsurance costs rose more than 100% from 2017 to 2023. This “reinsurance shock,” as they call it, forced insurers to pass their own costs to homeowner policyholders.

The insurance industry is just not making money, according to the Insurance Information Institute. In 2023, insurers paid out $1.11 in claims for every dollar they made in premiums. This year is expected to be the fifth year in a row with underwriting losses, the institute determined.

When these pressures mount to an intolerable level, insurers stop writing new policies, as companies have done in California, Florida and elsewhere. Policies written by state-based last-resort insurance plans doubled to 2.7 million from 2018 to 2023.

The Senate Budget Committee last week published what may be the most granular data available depicting a homeowners’ insurance market “already in the throes of crisis.” The data show “insurance upheaval” growing beyond well-known, frontline states, like Florida, North Carolina and California. Among them is Washington, which ranked 12th nationwide in 2023 for states seeing the fastest growth in non-renewing insurance policies.

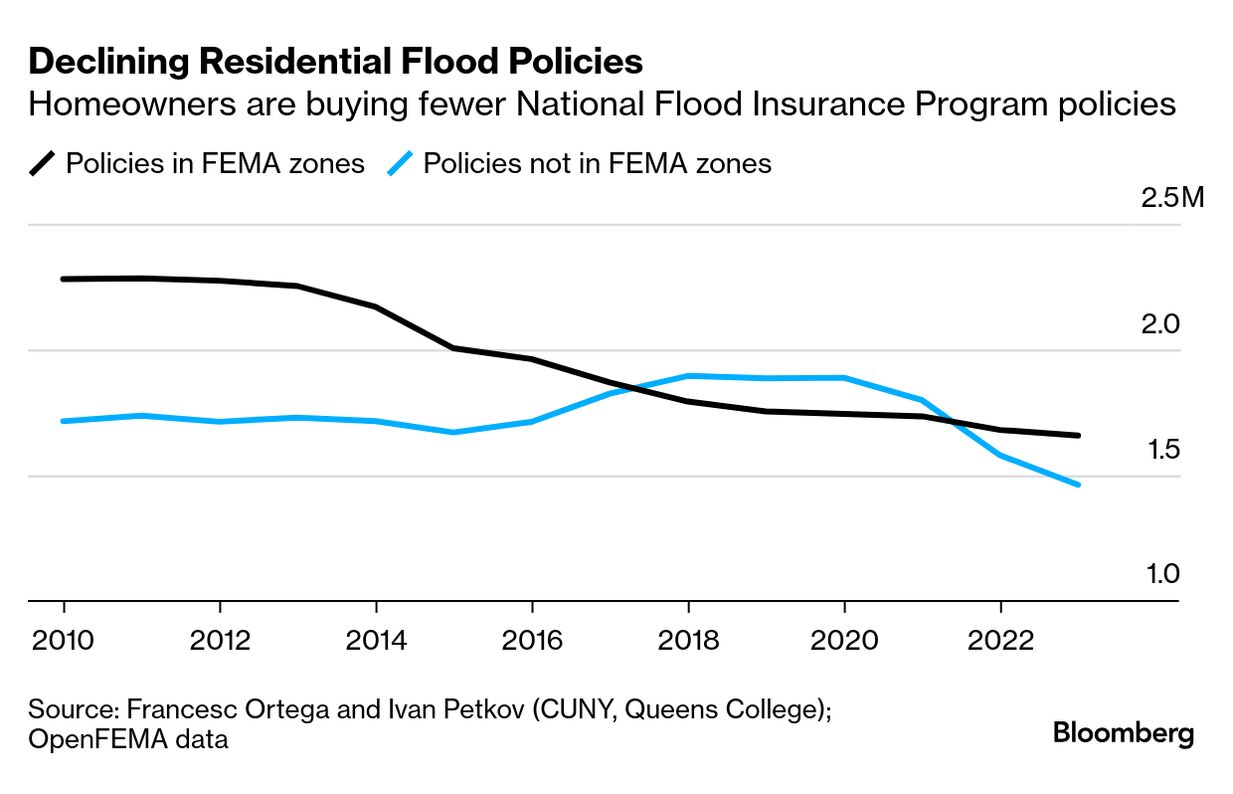

And that’s only the market for non-flood insurance. Flood insurance is mostly sold through the federal government, and only 4% of Americans have it. Rates have ticked up to reflect higher risk, but the system needs reforms beyond what the US is already undertaking, according to a Government Accountability Office note last month.

Declining Residential Flood Policies

Homeowners are buying fewer National Flood Insurance Program policies

Source: Francesc Ortega and Ivan Petkov (CUNY, Queens College); OpenFEMA data

Few people realize their home has the potential to flood. Buried deep on the Pierce County website was a nearly 20-year-old study about the Puyallup River. There was a chance, the study found, that the river could change course. That’s exactly what it did, veering directly into the Pelleys’ yard. But the little-known study hadn’t come up in due diligence.

Life is much warmer in the Pacific Northwest than it used to be. The Pelleys’ story may seem like an unlucky, cascading destructive fluke. It is, but so is that of post-Helene Asheville, and Florida’s Gulf Coast in the wake of Milton; and others. The odds of worsening extremes of every type, and their mutual compounding means that more families across the country are likely to see their homes become unlivable, with little to no recourse.

Outgoing Washington governor Jay Inslee has made climate issues a priority during his time leading the state. Photographer: Ruth Fremson/The New York Times/Redux

Jay Inslee, Washington’s outgoing governor, has been warning about climate change for decades and working to enact state policies to reduce emissions and the risk to his constituents. He knows there’s work to be done to protect homeowners.

“There are certain things we can do. We can help people understand the risk of flood and dissuade development and flood prone areas — and floods are going to increase because of climate change,” Inslee says. “And you’ve got a mortgage that, when your house doesn’t exist, the debt still exists. So it’s a horrific problem.”

The mortgage industry is not unaware of climate change. The Mortgage Bankers Association, the industry’s largest and most powerful lobbying group, commissioned in September 2021 a detailed report on the impact climate change will have on the sector it represents, offering up primarily bad news. The front page featured residential homes near the cliff edge of a melting iceberg.

“Chronic physical risk associated with climate change may also exceed the capacity of insurance and government assistance to sustain some areas,” the report determined. The group keeps up with economic and scientific studies, and regularly meets with representatives from the federal government.

Mike Fratantoni, chief economist at the Mortgage Bankers Association, says that methods to gauge the climate risk of a property are still evolving, and can’t by themselves swing a lending decision. “I don’t know that it really becomes an underwriting yes-or-no decision,” he says. The Pelleys say they would have walked away from the home had they known all the climate risks in full before purchase.

“The Federal Housing Finance Agency takes the threat posed by climate change to the housing finance system very seriously,” an agency spokesperson said in an emailed statement. “This commitment is reflected across the Agency’s work, including through its Climate Risk Committee, which was formed to ensure the Agency makes strategic and tactically sound decisions concerning the impacts of and response to the risks posed by climate change in a coordinated, collaborative, and informed manner in furtherance of FHFA’s mission.”

Shauna and Kevin Pelley envisioned retiring on the scenic property with their pets. Photographer: Grant Hindsley for Bloomberg Green

In an effort to front-run climate risk, FHFA requires Fannie and Freddie to “actively manage risk.” A company-wide climate committee monitors climate issues at Freddie Mac, with board oversight, and has been identifying data gaps and new ways to quantify risk. Fannie Mae declined to comment. The company has board- and management-level climate risk oversight and is looking at how its insurance requirements “promote the financial stability of households impacted by severe weather,” according to a recent financial filing.

FHFA could mandate that buyers are able to meet a more rigid financial profile proving they make more than enough income to sustain the home and will continue to do so even in a future with rising risks and costs. Burt suggests effectively pricing the median lifetime cost of insurance into the loan at the time of purchase. The GAO made a recommendation to Congress in 2021 to expand the mandatory insurance purchase requirement, but that also went nowhere.

“I think it’s a conspicuous gap,” Whitehouse says of the industry and the reality of climate change’s impact. “FEMA supports are almost inevitably insufficient. That leaves a significant incentive for the property owner to simply walk away and leave it as the mortgage holder’s problem. It’s an intense pressure on the mortgage guarantee companies like Fannie and Freddie.”

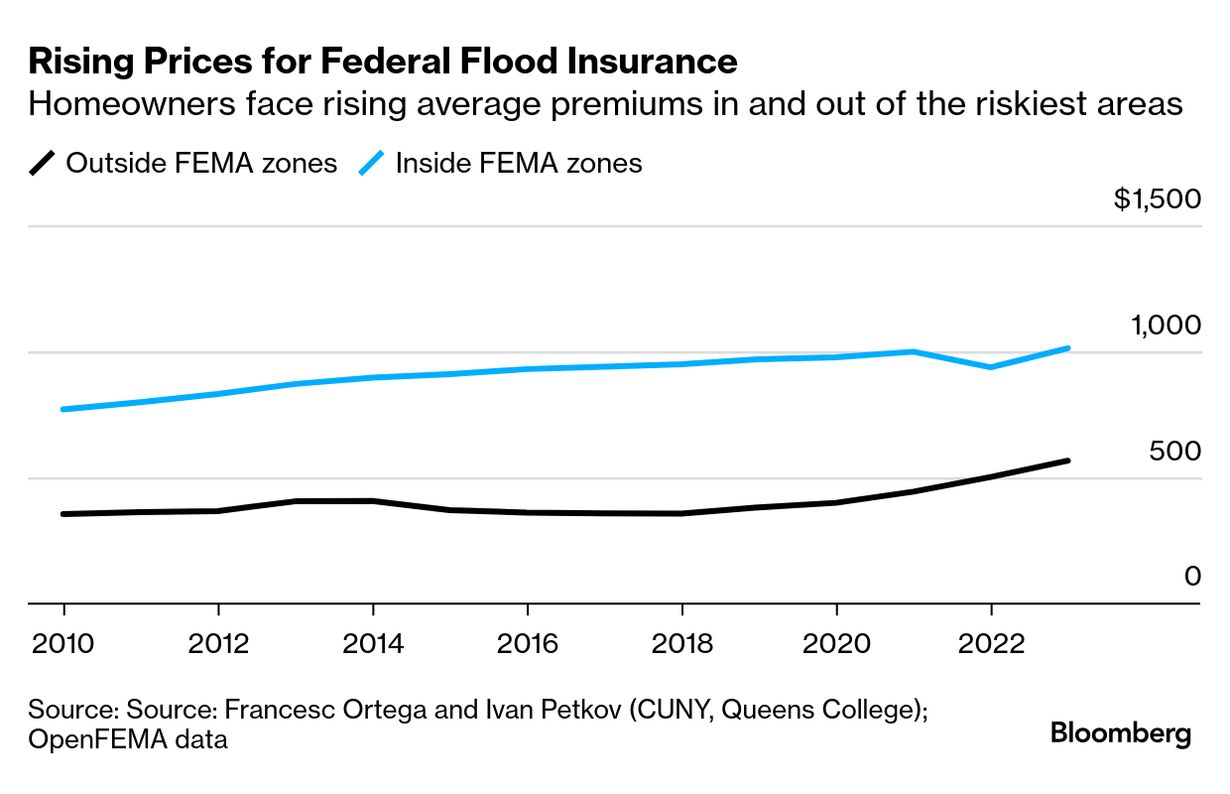

Rising Prices for Federal Flood Insurance

Homeowners face rising average premiums in and out of the riskiest areas

Source: Source: Francesc Ortega and Ivan Petkov (CUNY, Queens College); OpenFEMA data

The companies are regulated by Congress and take orders from America’s politicians. Making the industry take climate into account is a hard sell at the federal level, Whitehouse says. He worries that it would take another major natural disaster at the scale of a Hurricane Sandy or Katrina to get Congress to act. Even mundane, less catastrophic flooding is costing the federal government millions in mortgage-related costs: in July, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the GSEs, VA and Federal Housing Administration were going to lose $275 million in the 2024 fiscal year to flooding.

Helene, the kind of catastrophic event Whitehouse worried about, has spurred a slew of small FEMA payments, which average around $5,000 per homeowner. The token amount is nowhere near enough to rebuild most homes impacted by the storm to their pre-hurricane condition.

The long term winners, as Whitehouse sees it, are the lenders, who can keep doing business while borrowers continue to acquire homes in risky areas.

After they demolished their house, the Pelleys stopped paying their mortgage. They found a new house, drawing on their retirement to buy it, in a suburban neighborhood far above sea level. It has no fruit trees, bald eagles or hummingbirds. But it is safe from rivers.

Hoping to escape the debt of the river house, the Pelleys are navigating a deed-in-lieu of foreclosure process, which may tank their credit but hopefully keep them out of court. The VA said it recommends this over traditional foreclosure. If they succeed in that negotiation, they’ll still owe tens of thousands in demolition and preservation costs to the county, and even more to relatives who helped keep them afloat when they lost their home. If not, they’ll owe all that and about a half million dollars more.

They’ve appealed the insurance verdict, but it’s unlikely they’ll see a payout.

“There is a responsibility between government and the insurance industry to make sure if somebody is allowed by their government to purchase and build a residence, that there should be an insurance option for them,” Kevin says, reflecting on the busy hurricane season. “If they’ve allowed to build on it, and you own your home, there should be some political protection to remain insured.” —With Anna Edgerton

More On Bloomberg

Nguồn: https://propertytax.pics

Danh mục: News